Materials

This illustration of three people seated at dinner comes from Arnold of Villanova's treatise on winemaking (Italy, 14th century), which is on vellum.As Raymond Clemens and Timothy Graham explain in their Introduction to Manuscript Studies, "Parchment is literally the substrate upon which virtually all knowledge of the Middle Ages has been transmitted to us" (p. 9). Parchment, or stretched animal skin, was used more frequently than paper in manuscript production until the fifteenth century. Though parchment can be made from a variety of animal skins, calfskin, also known as vellum, provided the best quality medium for medieval manuscripts and was still preferred by many for high end early printed books during the Renaissance. All three of the fourteenth-century manuscripts in the Reynolds-Finley Library are on vellum. The Rhazes manuscript, copied in the early 1400s from a 1388 translation, is composed of both paper and parchment, an example of the transition period between the two mediums. Finally, the manuscripts in the collection from the later fifteenth and sixteenth centuries are on paper. New paper production methods created in Italy in the late fourteenth century dropped the price of paper, setting the conditions for its preference at the arrival of printing in 1450.

This illustration of three people seated at dinner comes from Arnold of Villanova's treatise on winemaking (Italy, 14th century), which is on vellum.As Raymond Clemens and Timothy Graham explain in their Introduction to Manuscript Studies, "Parchment is literally the substrate upon which virtually all knowledge of the Middle Ages has been transmitted to us" (p. 9). Parchment, or stretched animal skin, was used more frequently than paper in manuscript production until the fifteenth century. Though parchment can be made from a variety of animal skins, calfskin, also known as vellum, provided the best quality medium for medieval manuscripts and was still preferred by many for high end early printed books during the Renaissance. All three of the fourteenth-century manuscripts in the Reynolds-Finley Library are on vellum. The Rhazes manuscript, copied in the early 1400s from a 1388 translation, is composed of both paper and parchment, an example of the transition period between the two mediums. Finally, the manuscripts in the collection from the later fifteenth and sixteenth centuries are on paper. New paper production methods created in Italy in the late fourteenth century dropped the price of paper, setting the conditions for its preference at the arrival of printing in 1450.

Illuminations

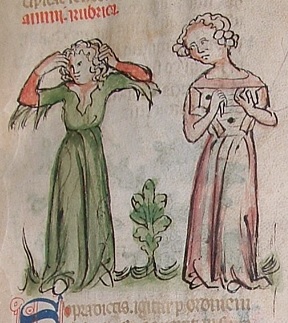

Illustration of two women from the Arnold of Villanova manuscriptThe term illumination originally referred to medieval book illustrations using gold and silver, which would illuminate the often religious subjects of the paintings. However, the term has come to refer to any illustrated work of the period. By the late Middle Ages, illuminations were no longer created by the scribe as seen in earlier medieval works, but instead, specially trained artists known as illuminators or miniaturists. It is interesting that extant receipts from book production indicate they were paid considerably less than scribes (Walther & Wolf, p. 21), despite the beauty and intricacy of their art and the value it added to a manuscript. Nevertheless, in the pre-printing age, the knowledge conveyed through the scribe's text was the essential part of the book. Whereas the names of scribes were often recorded, the illuminators' almost never were.

Illustration of two women from the Arnold of Villanova manuscriptThe term illumination originally referred to medieval book illustrations using gold and silver, which would illuminate the often religious subjects of the paintings. However, the term has come to refer to any illustrated work of the period. By the late Middle Ages, illuminations were no longer created by the scribe as seen in earlier medieval works, but instead, specially trained artists known as illuminators or miniaturists. It is interesting that extant receipts from book production indicate they were paid considerably less than scribes (Walther & Wolf, p. 21), despite the beauty and intricacy of their art and the value it added to a manuscript. Nevertheless, in the pre-printing age, the knowledge conveyed through the scribe's text was the essential part of the book. Whereas the names of scribes were often recorded, the illuminators' almost never were.

A plate, a wine-glass, and a fish on a dish, upon a table laid with a cloth, from Arnold of Villanova's manuscriptIlluminators were skilled artists, but the process was very technical as well. They usually created preliminary artistic designs that were recreated on the text using reproduction methods such as an early form of tracing paper. But some were copied from pattern books or the work of respected illustrators. These illustrators were also trained in the preparation of gold leaf and the concoction of paint from minerals, plants, animals and binding mediums (Walther & Wolf, p. 22). See the 26 miniature illustrations from Arnold of Villanova's Regimen Sanitatis ad Regem Aragonum in the Reynolds-Finley Library for examples of the art of illumination.

A plate, a wine-glass, and a fish on a dish, upon a table laid with a cloth, from Arnold of Villanova's manuscriptIlluminators were skilled artists, but the process was very technical as well. They usually created preliminary artistic designs that were recreated on the text using reproduction methods such as an early form of tracing paper. But some were copied from pattern books or the work of respected illustrators. These illustrators were also trained in the preparation of gold leaf and the concoction of paint from minerals, plants, animals and binding mediums (Walther & Wolf, p. 22). See the 26 miniature illustrations from Arnold of Villanova's Regimen Sanitatis ad Regem Aragonum in the Reynolds-Finley Library for examples of the art of illumination.

Marginalia

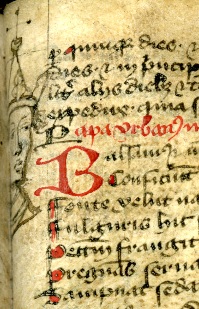

Illustration in the margin of Petrus Peregrinus' Tractatus de Magnete (England, 14th century)"Unpredictable, topical, and often irreverent, like the New Yorker cartoons of today, marginalia must have been a source of great delight for medieval readers," says Margot McIlwain Nishimura in her book Images in the Margins. Sometimes relevant to the content, marginalia are just as often playful and whimsical manifestations of imagination with no connection to the subject matter of the serious works they accompany. Created using the same materials and techniques as other illuminations, they were clearly original to the manuscripts but themed less similar to the particular works they inhabit than to marginalia themes found throughout manuscripts, primarily those of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

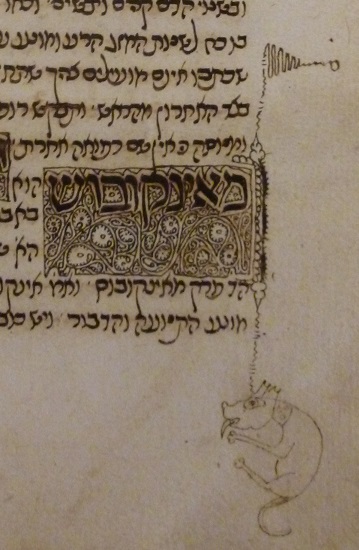

Marginalia from Rhazes' Al' Mansuri (Portugal, 1388)Animals and humans falling off the page and strange hybrid creatures are common. The Rhazes manuscript at the Reynolds-Finley Library is decorated with a number of interesting marginalia, such as hybrid figures and a dog suspended from rubricated letters.

Marginalia from Rhazes' Al' Mansuri (Portugal, 1388)Animals and humans falling off the page and strange hybrid creatures are common. The Rhazes manuscript at the Reynolds-Finley Library is decorated with a number of interesting marginalia, such as hybrid figures and a dog suspended from rubricated letters.