Exercitatio anatomica de motu cordis et sanguinis in animalibus. Francofurti, sumpt. Guilielmi Fitzeri, 1628.

Before the discoveries of William Harvey, the prevailing theory on blood circulation was based on Galen’s ideas. According to this tradition, blood is produced by the transformation of food in the liver. Blood is then distributed to the rest of the organs by way of veins originating in the liver, and absorbed for organ nourishment (Cambridge 158). By 1500, this theory was being called into question by a few innovative scientists, such as Servetus who described pulmonary circulation and Cesalpinus who speculated about blood circulation (Clendening 152). But none was able to scientifically prove the true nature of the circulatory system until Harvey did in his Exercitatio anatomica de motu cordis et sanguinis in animalibus, better known as De motu cordis.

Before the discoveries of William Harvey, the prevailing theory on blood circulation was based on Galen’s ideas. According to this tradition, blood is produced by the transformation of food in the liver. Blood is then distributed to the rest of the organs by way of veins originating in the liver, and absorbed for organ nourishment (Cambridge 158). By 1500, this theory was being called into question by a few innovative scientists, such as Servetus who described pulmonary circulation and Cesalpinus who speculated about blood circulation (Clendening 152). But none was able to scientifically prove the true nature of the circulatory system until Harvey did in his Exercitatio anatomica de motu cordis et sanguinis in animalibus, better known as De motu cordis.

William Harvey was a native of Folkstone, England. He studied medicine at Cambridge, and then later at Padua under the professor, Fabricius, whose work on venous valves was instrumental in the development of Harvey’s theory. In Padua, Harvey first began to investigate the functions of the heart, and even as early as 1603, he was hypothesizing that heart beats caused the circulation and movement of the blood (Cambridge 159). After receiving his medical degree, Harvey returned to England, practiced and taught at the College of Physicians in London, and shared this theory in his lectures (Not. Med. Books 63). After years of reviewing all literature on the subject, experimenting on many different animals, and using inductive reasoning based on these observations, Harvey was able to announce his proof in the 1628 publication, De motu cordis. Central to his argument are the results of measurements and calculations of blood volume and velocity. He demonstrates with these mathematical figures that it is impossible for the liver to produce enough blood from average daily food intake to make up for circulation (Duffin 47). The only other solution is that it continuously circulates, propelled by heart beats and returning to the heart by way of the veins. This was the first application of measurement to biological study (Garrison 247).

Harvey’s work was not immediately accepted, and it resulted in public refutations and a decline in his practice. But by the time of his death, the theory had gained appreciation (One Hund. Books 27). The Reynolds-Finley Library has a very rare first edition copy of this famous book, which is arguably the most important work in medical history (Heirs of Hippocrates 256). There are fewer than 70 known copies of this edition in existence, probably due to it being printed on thin and now deteriorating paper (One Hund. Books 27). Published in Frankfort, a great center of learning in those days, this book includes illustrations of venous valves in the arm based on Fabricius’s drawings (Reynolds 1886).

Cambridge. Illus. Hist. Med., p. 159; Clendening, Source Book of Med. Hist., p. 152; Duffin, Hist. of Med., pp. 45-47; Garrison, Hist. of Med., 4th Edition, pp. 246-247; Garrison & Morton, Med. Bib., 5th Edition, 759; Heirs of Hippocrates, 256; Not. Med. Books, 63; One Hund. Books, 27; Reynolds Historical Library, Rare books and coll…,1886.

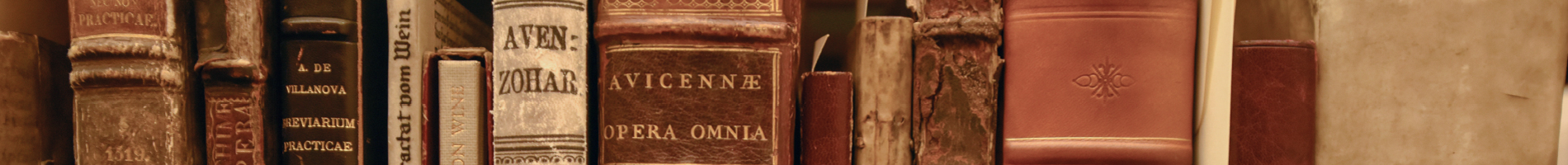

Image: William Harvey, Print Collection, Reynolds-Finley Historical Library.