Reynolds-Finley Section

A journal of hospital life in the Confederate Army of Tennessee, from the battle of Shiloh to the end of the war: with sketches of life and character... Louisville, KY: John P. Morton & Co., c1866.

One of the very few accounts of the work of Confederate women during the Civil War is Kate Cumming’s A journal of hospital life in the Confederate Army of Tennessee. A copy of this journal, published in 1866, is held at the Reynolds-Finley Historical Library. It provides us with extensive knowledge of the role of women in Confederate hospitals, written from the perspective of a woman who served in a nursing capacity from 1862-1865. It is also the most complete and detailed narrative of Confederate hospital life known (Harwell xv-xvi).

One of the very few accounts of the work of Confederate women during the Civil War is Kate Cumming’s A journal of hospital life in the Confederate Army of Tennessee. A copy of this journal, published in 1866, is held at the Reynolds-Finley Historical Library. It provides us with extensive knowledge of the role of women in Confederate hospitals, written from the perspective of a woman who served in a nursing capacity from 1862-1865. It is also the most complete and detailed narrative of Confederate hospital life known (Harwell xv-xvi).

Kate Cumming was born in Scotland and, as a child, moved to America with her large family, first to Montreal, then to New York, and finally in the 1840’s to Mobile, Alabama. There she spent the remainder of her youth and early adulthood. By the 1860s, Cumming had been in the South for many years and identified the Confederacy as home and “the cause” as her own (Heidler & Heidler 5: 528-529). Several months after the start of the Civil War, Kate was much inspired by an address given by family friend, Reverend Benjamin M. Miller, at a local church. In his speech, Miller called for Southern ladies to help the wounded and sick by becoming nurses at the war front. Cumming was discouraged from volunteering by her respectable Southern family, who thought that “nursing soldiers was no work for a refined lady,” (qtd. in Harwell x). Therefore, initially she relegated her involvement to assisting other volunteers in their preparation to leave for the hospitals. However, when a regiment of old school and church friends were sent off to war, Cumming was compelled to offer her services to Mr. Miller despite her family’s disapproval and her own lack of hospital training. In April of 1862, Mr. Miller summoned his volunteer ladies to head north to Mississippi to help those returning from the battle at Shiloh (Harwell x).

Conditions in the hospitals of Okolona and Corinth, Mississippi were so horrible that only Cumming and one other nurse stayed beyond a week. Despite the hardships, Kate remained through June and returned to serve in Chattanooga that fall. Her duties were many faceted — delivering food and medicine, managing laundresses, writing letters, keeping clothing and bedding fresh, and even cooking (Heidler & Heidler 5: 529). In September of 1862, new laws allowed the employment of women to be officially recognized by the Confederate medical department, and at that time, Cumming received the rank of matron, or hospital supervisor (Notable American Women). She worked in Chattanooga until the summer of 1863, and then traveled with Surgeon Samuel Stout’s medical corps in the Army of Tennessee, which was constantly moving as General Sherman swept through Georgia and the Carolinas (Heidler & Heidler 5: 529). Stout was first hesitant to accept the role of women in the hospital, but was soon convinced, and commended them in his personal narrative. He specifically names Cumming and two others as “the first refined, intellectual, self-denying ladies, who in the midst of the suffering soldiers, served at their bunkside at night as well as day. Their self-denying and heroic benevolence inspirited many other educated and refined ladies to imitate their examples,” (qtd. in Harwell xii).

While traveling with the Army of Tennessee, Cumming faithfully recorded her experiences in a journal, which became her great contribution to history. Hastily published within a year of her return to Mobile after the war, Kate Cumming’s journal did not receive the readership it deserved, perhaps because it was too close to the events or because of the influx of Confederate narratives at the time (Harwell xv). However, the journal is invaluable from a historical perspective because it is the most complete and realistic record of the workings of Confederate hospitals and the services of matrons. Later, in 1890, she republished the journal under the title, Gleanings from Southland. This shortened, edited version experienced more success in a market “hungry for ‘the romance of reunion’” (Heidler & Heidler 5: 529). Cumming moved to Birmingham in 1874, where she remained until her death in 1909.

Image: Kate Cumming, Gleanings from Southland (1895), Reynolds-Finley Historical Library.

A manual of military surgery: for the use of surgeons in the Confederate Army. Richmond, VA: West & Johnson, 1861.

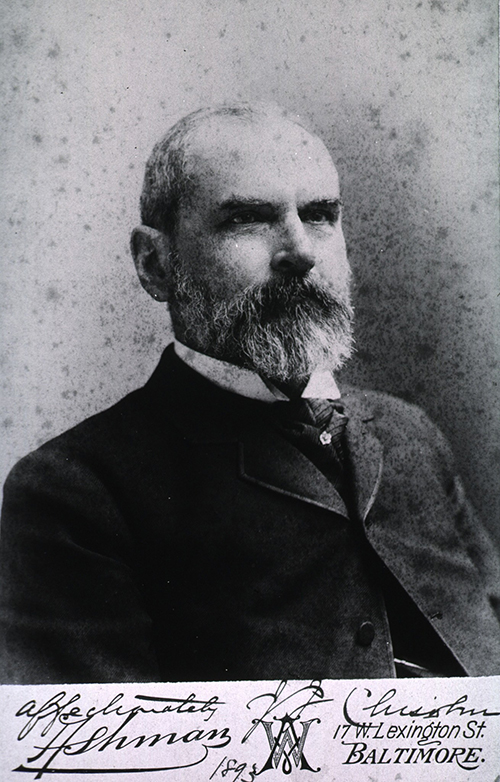

Julian John Chisolm, a native of Charleston, South Carolina, attended the medical college of his home state. Like many doctors of the time, he received further post-graduate education in France, where he visited the most famous clinics and came into contact with the leaders of the new so-called “Paris medicine” at the cutting edge of his field. These experiences left a lasting impression on the young physician. In 1858, Chisolm was named Professor of Surgery at the Medical College of the State of South Carolina, which was considered the most important medical school south of Philadelphia at that time (Atkinson 216). He was a conscientious professor, known for holding weekly conferences with the graduating class to allow for closer teacher and student interaction. In 1859, Chisolm traveled again to Europe, and was in Milan when troops began returning from the battlefields of the war between Austria and Italy. Thus, he had the opportunity to observe military hospitals and their treatment of the wounded (In honor of Julian John Chisolm 2). Not long after his return, the American Civil War broke out, and he had the opportunity to use this valuable knowledge obtained from his travels. Chisolm was called to duty as army surgeon for the Confederacy in 1861.

Julian John Chisolm, a native of Charleston, South Carolina, attended the medical college of his home state. Like many doctors of the time, he received further post-graduate education in France, where he visited the most famous clinics and came into contact with the leaders of the new so-called “Paris medicine” at the cutting edge of his field. These experiences left a lasting impression on the young physician. In 1858, Chisolm was named Professor of Surgery at the Medical College of the State of South Carolina, which was considered the most important medical school south of Philadelphia at that time (Atkinson 216). He was a conscientious professor, known for holding weekly conferences with the graduating class to allow for closer teacher and student interaction. In 1859, Chisolm traveled again to Europe, and was in Milan when troops began returning from the battlefields of the war between Austria and Italy. Thus, he had the opportunity to observe military hospitals and their treatment of the wounded (In honor of Julian John Chisolm 2). Not long after his return, the American Civil War broke out, and he had the opportunity to use this valuable knowledge obtained from his travels. Chisolm was called to duty as army surgeon for the Confederacy in 1861.

Many of the Confederate military surgeons were general practitioners with insufficient experience treating gunshot wounds, and the South had no handbook on military medicine. During the previous years of peace, there had been little interest in writing on the subject of soldiers’ health, and almost immediately after the war began, the South was blockaded from communication with Europe. With the South cut off from critical information from Europe and with pressing medical needs brought on by war, in 1861 Chisolm wrote A manual of military surgery to fulfill the demand (Chisolm iii). The Reynolds-Finley Historical Library includes this book, which quickly became a standard text for Southern army surgeons and went through three editions. The book provides surgical instructions and advice on treating the sick and wounded on and off the field. It addresses issues such as food, clothing, hygiene and even amusement for the continuing health of soldiers. In writing this work, Chisolm relied upon knowledge gained during his excursions in Europe and on the medical publications acquired therein (Chisolm iv).

While serving the Confederacy, Chisolm also became known for inventing a chloroform inhaler which was used heavily throughout the war. He was later employed as medical purveyor and director of a Confederate pharmaceutical plant. After the war, Chisolm moved to Baltimore, Maryland in 1868, and soon joined the medical faculty of the University of Maryland. He held several important positions at that university over the next 28 years, including Dean of the Medical School, Chair of Operative Surgery and Professor of Diseases of the Eye and Ear. Most of his academic career in Maryland was devoted to ophthalmology, and he became an eminent figure in this field, publishing many works on the topic. Among his thankful clients was Helen Keller whose father brought her to Chisolm for consultation, and to whom he gave hope and guidance by suggesting that Helen be taught despite the fact that she would never see or hear (In honor of Julian John Chisolm 18). Also, he left a lasting impression upon his many admiring students. He retired from the University of Maryland in 1896, and became a Professor Emeritus.

Image: Julian John Chisolm, Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.

The Red Cross; a history of this remarkable international movement in the interest of humanity. Washington: American National Red Cross, 1898.

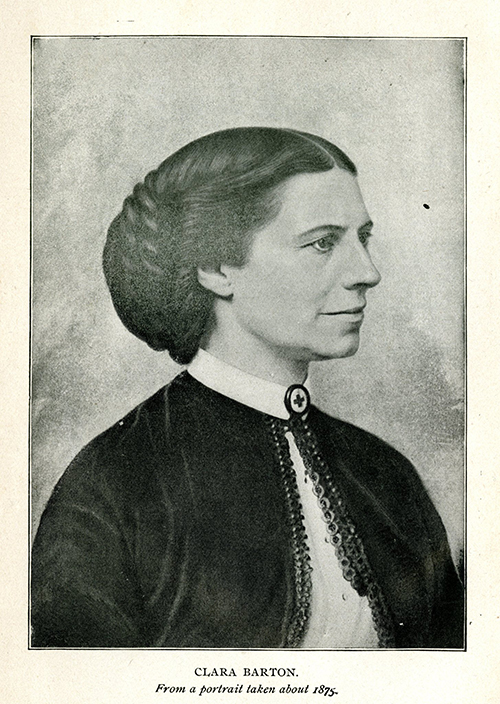

In her hometown of Oxford, Massachusetts, Clara Barton began serving humanity early in life when she set up a school for the children of her father’s sawmill workers in 1836. She was only fifteen years of age (Library of North American Biographies). Departing from this position in 1851 to enhance her education, Barton attended school at the Liberal Institute of Clinton, NY for one year. Thereafter, she found herself teaching again in Bordentown, NJ from 1852 to 1854. Clara’s school in Bordentown was one of New Jersey’s first free, public schools, and its great success and growth in such a short period of time caused the local school board to hire a male principal to supervise. This action, however, upset Clara, prompting her to leave her job and teaching career behind. Her departure has been described as "a tactful, characteristic display of independence" (American Reformers). But soon, with the help of her congressman, Barton secured a job with the Patent Office in Washington in 1854, becoming the first regularly appointed female civil servant (Notable American Women). These actions from Clara’s early years show a dedication to work and a pioneering spirit.

In her hometown of Oxford, Massachusetts, Clara Barton began serving humanity early in life when she set up a school for the children of her father’s sawmill workers in 1836. She was only fifteen years of age (Library of North American Biographies). Departing from this position in 1851 to enhance her education, Barton attended school at the Liberal Institute of Clinton, NY for one year. Thereafter, she found herself teaching again in Bordentown, NJ from 1852 to 1854. Clara’s school in Bordentown was one of New Jersey’s first free, public schools, and its great success and growth in such a short period of time caused the local school board to hire a male principal to supervise. This action, however, upset Clara, prompting her to leave her job and teaching career behind. Her departure has been described as "a tactful, characteristic display of independence" (American Reformers). But soon, with the help of her congressman, Barton secured a job with the Patent Office in Washington in 1854, becoming the first regularly appointed female civil servant (Notable American Women). These actions from Clara’s early years show a dedication to work and a pioneering spirit.

However, Barton’s humanitarian pursuits truly began when the Civil War broke out. First she came to the aid of Union soldiers who found themselves in Washington after being attacked at Baltimore. Many were wounded and without supplies, and so Clara placed advertisements in the newspaper for medicines, bandages, food and clothing donations. Initially she used her own rooms to store the abundant contributions. Soon her service expanded and she rented a warehouse to keep supplies, which she insisted upon personally delivering to the battlefields. The War Department at first objected to a female presence on the field, but her persistence won them over, and she eventually secured army carts and mules to aid in her distribution. Barton also prepared meals for the soldiers and nursed the sick and wounded, earning the name “Angel of the Battlefield”. Only for a brief time in 1864 was she affiliated with the army in any official capacity. During this year she was head nurse with the Army of the James under General Benjamin Butler (American Reformers). Otherwise, Clara preferred to remain independent of the official United States Sanitary Commission and Dorothea Dix’s division of nurses (Notable American Women).

At the war’s end, Clara set up a missing soldier’s bureau with the approval of President Lincoln. Then from 1866 to 1868, she traveled around the northern and western parts of the United States speaking about her war experiences. In 1869, Clara went to Europe for health-related reasons and there became familiar with the International Committee of the Red Cross. This organization was formed during a convention in Geneva in 1863 and became official when the Geneva Treaty was ratified by eleven European countries in 1864. These countries agreed that in future wars, the wounded, ambulances and sanitary personnel would be neutral. Clara Barton believed strongly in the ideals of the Red Cross and joined them in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71) relief effort (American Reformers; Notable American Women). In 1877, she began a five-year campaign to initiate an American Red Cross. Some Americans clung to the Monroe Doctrine, a policy that said the United States should stay out of foreign affairs. And also, there was a general belief amongst the American people that their country would not face a war on their own ground again (Library of North American Biographies). However, Barton overcame these obstacles by appealing to the American need for peacetime disaster relief. Not only did her campaign result in the establishment of the American Red Cross in 1881, it also convinced President Chester A. Arthur to ratify the Geneva Treaty in 1882. Her suggestion for peacetime relief, known as the “American Amendment,” was adopted by the international organization. Clara Barton became the first president of the American Red Cross, a position she held until 1904.

A copy of Barton’s important book, The Red Cross; a history of this remarkable international movement in the interest of humanity, published in 1898, is held at the Reynolds-Finley Historical Library. The story recounts the establishment of the organization in Europe and its adoption by the United States. It also gives detailed accounts of specific early American relief efforts, during the Michigan forest fires, the Mississippi and Ohio River floods, the Texas Famine, the Johnstown Flood, the Russian Famine, the Spanish-American War, and several others. In 1899, this book was reprinted under the title The Red Cross in Peace and War, and the Reynolds-Finley Library also has a copy of this book.

Image: [From] Barton, Clara. The Red Cross; a history of the remarkable international movement in the interest of humanity. Washington: American National Red Cross, 1898; Reynolds-Finley Historical Library.

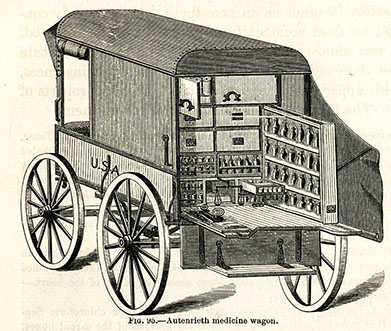

Image: United States Army medicine wagon from the Civil War; [From] Reports on the extent and nature of the materials available for preparation of a medical and surgical history of the Rebellion. United States Surgeon General's Office, Circular No. 6, 1865; Reynolds-Finley Historical Library Arnold G. Diethelm American Civil War Medicine Collection.