Reynolds-Finley Section

The following article is taken from Cholera Epidemic of 1873 in the United States. The Introduction of Epidemic Cholera Through the Agency of the Mercantile Marine: Suggestions of Measures of Prevention. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1875. (pp. 409-414). Included in this work is a section on the cholera epidemic which ravaged and nearly destroyed the young city of Birmingham, Alabama in 1873, together with a full-page map which has been described as "one of the earliest published maps of this city." The author of the article, Mortimer H. Jordan (1844-1889) was secretary of the Jefferson County Medical Society of Birmingham, Alabama in 1873 (during the epidemic) and later president of the Jefferson County Medical Society (1881-1883).

JEFFERSON COUNTY

CHOLERA AT BIRMINGHAM, ALA., IN 1873

BY M.H. JORDAN., Member of the Board of Health

In reporting a history of the recent epidemic of cholera as it prevailed at Birmingham, I will not discuss any theories nor indulge in any idle speculation, but will contain myself strictly to a simple, concise, narrative of events.

Our little city was terribly scourged for long weeks; our citizens became panic-stricken; many left, almost depopulating the town, and leaving the sick and indigent principally in the care of clergymen and physicians. The latter class, however, did not escape the disease, but two of their number lay for many days and nights upon the brink of the river, and it was only by the intervention of an all-wise Providence and the assiduous care of their attendants, that they recovered.

Birmingham is located in Jones Valley, near the center of Jefferson County, with the Red Mountains lying a short distance to the south and east, and what is known as Reservoir Ridge to the north and west. The stone near the surface is blue limestone, covered with a stiff clay soil, such as is usually found in the hilly portions of Central Alabama. The bed of the valley is formed by the old Silurian limestone, which doubtless was brought the surface through the super-incumbent strata, and is found throughout the entire valley, almost on edge, dripping, as we recede from the valley, to the northeast and southwest. From this fact we are led to conclude that the only water that appears on the surface or is found in wells in this valley must be surface-water, for the strata of limestone are not water-bearing, and only afford such supply of water as may have filtered throughout the strata of earth overlying the edges of this formation during the winter months, which finds a ready outlet in a southwest direction along the line of upheaval. This water find numerous outlets at various points in the valley, as is shown by the location of the springs, to be seen on the accompanying map all of which, with others northeast and southwest of Birmingham, are situated on the line of upheaval. Birmingham is a railroad center, having about three thousand inhabitants, a large number of whom live in houses closely crowded together, and in defiance of sanitary laws. Each day four railway trains pass through this town, making direct connection with Nashville, Chattanooga, and Louisville, in the north, and Montgomery, Mobile, and New Orleans, in the south. In addition, from six to eight freight-trains each day receive and discharge freight. The mineral interests in the neighboring mountains attract to the town many strangers, and during the summer months the transient population is quite large.

The ground upon which the city is located is undulating, with many elevations and depressions, in some places affording line natural drainage; in other it is low and marshy, and remains damp throughout the entire year.

The inhabitants of Birmingham were in 1873 supplied with water from two sources. A most admirable system of water-supply had been instituted, but the work had only advanced sufficiently to supply a small portion of the city. This supply was obtained from a large creek northeast of the city, distant nearly two miles, and separated from Jones Valley by a high ridge over one mile from the center of the city.

The inhabitants who could not yet reach this water supply, made use of several public wells and springs within the city limits, or were obliged to haul it from springs at the foot of Red Mountains. The public wells and springs referred to were in low, damp places, and so situated that they received the washes from a large surface of ground; and it was only at such points that water could be obtained. For that portion of the city north of the railroad, being built over the greatest dip of the limestone rock, water could not be obtained. South of the railroad, where the rock-bed is nearer the surface, water is obtained from private wells. But one house in the city was supplied with a water-cistern.

In the eastern portion of the city there is a pond, (marked A,) from which flows a small branch, which takes a westerly direction, crosses Twentieth street through a culvert, and continues in the same direction to the corner of Seventeenth street and Second avenue, where it unites with two other small branches from the south side of the railroad, (marked B and C.) At their junction these streams spread out and form a low, marshy ravine, overgrown a portion of the year with tall grasses, which continues in the same direction beyond the limits of the corporation. On the northern side of this ravine, (marked E) from Eleventh to Fourteenth street, which pass along a hill-side, a number of shanties and negro cabins, low, dirty, and ill ventilated, were located, which were known as "Baconsides". By each rain-fall the filth of all kinds which covered the ground around these cabins was washed into the ravine, and it was from a low spring and a number of barrels sunk in the marshy bottom of this ravine that the inhabitants of Baconsides and many of the white residents of Birmingham obtained their drinking water.

Until the alarm of cholera was sounded upon the streets, no effort was made by the city authorities to clean the streets and alleys, to drain and disinfect cess-pools, and wet places, nor had cleanliness been demanded in privies and stables. The first case of cholera that occurred in Birmingham in 1873 was in the person of a Mr. Y., who was taken sick on the 12th day of June and died after an illness of twenty-four hours. He was an able-bodied man, who had been in the city about six weeks, and had been perfectly healthy until the arrival of his bed and bed-clothing, which had been shipped to him from Huntsville, and which were received and used by him three days before he was taken with the disease; and it was subsequently determined that these articles had been used in the portion of the city of Huntsville that was infected with the disease. Y. Was taken with cholera at the point marked 1 on the map. His physicians had no suspicions that he had cholera at that time, although his symptoms greatly resembled it, as there had been no cases of the disease in this section of the state. No care was taken to disinfect the discharges, which were thrown on the ground in the rear of the house, on the slope of the hill, immediately above the branch marked D. No other cases occurred until June 17, when a young girl named, Hughes and her sister were taken with cholera within a few hours of each other, and both died within twenty-four hours. The home of these children (see map 2) was in a miserable little hovel near the edge of a small branch (marked F) which runs through several acres of low, marshy ground. It was determined that the different members of this family had been constantly at the house of Y., the first case, during his illness. The discharges from these patient were not disinfected, but were thrown into the branch, which flows down to the same marshy ground from which the inhabitants of "Baconsides" obtained their drinking water. June 19, a man named Bennett, who was a shoemaker, and lived at the point marked 4 on the map, was taken with cholera, and died after an illness of eighteen hours. This man had been absent from home for several weeks and returned, suffering with an acute diarrhoea, from Chattanooga the night previous to his attack. The discharges in this case were disinfected, and the bed and bed-clothing were burned. Under the house in which this man died was a damp, filthy cellar, which had been nearly full of water in the early spring. June 20 a comrade of Bennett, who had waited upon him in his illness and had carried out the discharges, was taken with cholera, and died in twelve hours. The excreta were disinfected and buried. June 21, a sister-in-law of Bennett, who was constantly with him until his death, was taken with cholera at her house, (marked 6) and died in twenty hours. The discharges of this patient were not disinfected, but were thrown into the branch in rear of the house. June 22, a negro boy was found in a low, dirty shanty close by the line of the Alabama and Chattanooga Railroad, (marked 7,) in a state of collapse, and he died in a few hours. In the evening of the same day a negro named Edwards was taken with the disease at his home on the banks of the ravine marked C. The disease was fully developed, but reaction was established and he recovered. June 23, a negro named Eubank was taken with the disease at the residence of a gentlemen, (marked 9.) He had copious rice-water discharges, cold skin, profuse perspiration, small, frequent pulse, and cramps in the extremities; he responded to the treatment and recovered. Great care was taken to disinfect and bury the excreta. He was kept as much isolated as possible, and no other case was developed on the premises or in the immediate neighborhood. On the same day several cases of cholera occurred at Baconsides, all of which terminated fatally within twenty hours. No disinfectants were used; the excreta were thrown upon the ground; the epidemic was inaugurated, and deaths occurred in every household. At first all of the negroes in this portion of the city who took the disease invariably died within a few hours; but when the violence of the epidemic began to subside, many recovered. Along the banks of the branch marked C upon the map are a number of cabins, in one of which Edwards, the case of June 22, had the disease, and in one of these cabins, on the 24th, Minerva, a negro girl who had nursed Edwards and carried out his dejections, was attacked, and died within ten hours. Before this girl's body was buried, two other cases occurred in the same cabin, which rapidly proved fatal. The discharges in these cases were disinfected and buried, and by order of the board of health the beds and bed-clothing were burned. The occupants of all the cabins upon the line of this branch suffered so severely with the disease that they were abandoned. June 27, Hughes, the father of the two girls who died upon the 17th, was taken with cholera, and died on the following day; the third death in the same house, out of a family of five individuals. July 1, cholera was declared epidemic over the entire city of Birmingham, and it is now impossible to give step by step the progress of the disease, for the spread of the disease was so rapid and its virulence so great that the physicians could take no time to record cases. July 2, Mr. M., who was a clerk in the city, but who slept at his home at Elyton, distant two miles, was attacked with cholera, and died within ten hours. The excreta of this case were disinfected with carbolic acid and buried. No other case of the disease occurred in the village. July 4, an excursion party of about two hundred citizens of Birmingham visited Blount Springs, some thirty-odd miles north, on the line of the South and North Alabama Railroad. They spent the day in eating, drinking, dancing, &c., and returned to Birmingham about 8 o'clock in the evening. Before daylight the next day seven of their number had died of cholera. July 7, a Mrs. H. Had slight symptoms of diarrhoea, and concluded to go to the house of her father-in law, who lived on the top of Thodes Mountain, distant about eight miles. The next day she was taken with cholera, and died in twenty-four hours. Her mother-in-law, who nursed her carefully until her death, was taken with cholera July 10, and died in twelve hours. The discharges from these cases were received upon cloths, which were washed out, and the water thrown upon the grass in the back-yard, but after the arrival of a physician they were disinfected and buried, and the bed and bed-clothing were burned. No other cases of cholera were developed in this family, although several members of it suffered from diarrhoea. July 9, was called to see Lee Anderson, the carriage-driver of Colonel T., who lived in an elevated portion of the city, in which there had been to this time no cholera, and found him with the symptoms of the disease strongly defined. This man had remained well until he had visited some of his friends at Baconsides. His system responded to the remedies exhibited, and late in the evening he had fully reacted, but the next morning at an early hour was found fully collapsed. It was discovered that during the night he had several times left his bed and had gone to the cistern on the premises for drink, and that he had several dejections in the yard, which were not disinfected. He died in a few hours. July 10, Colonel T., his wife, and several members of his family were taken with diarrhoea, which, with the exception of Mrs. T., yielded readily to the remedies used. This lady, however, fearing that the medicine might injure her sucking child, concluded to does herself with Simmons's liver regulator, a proprietary medicine much in vogue throughout the Southwest; and the next day an attack of cholera was fully developed. She however reacted, and for several days seemed convalescent; her dejections contained bile; the secretion of urine was re-established, but on the fifth day she sank and died. This lady had been exposed to the disease by assisting in washing and dressing the body of a Mrs. K., who had died of cholera a few days previously in another portion of the city. The premises of Colonel T. was one of the few in the city which were provided with cisterns of rain-water, and the generous owner, thinking that cistern-water was the safest for drinking purposes, allowed free access to his water-supply to all in his neighborhood. In this portion of the city no cases of the disease had occurred until after the negro Anderson's visit to Baconsides; but after his death the persons who used this cistern-water, and the immediate neighborhood of Colonel T.'s property, suffered as severely, if not worse, than any other portion of the city.

The most popular hotel in the city, located close to the line of the railroads, around which the disease prevailed, escaped the disease. This house is built upon pillars several feet above the surface of the ground, allowing free ventilation. The drainage was admirable, the water-supply good, and the proprietor spared neither time nor expense in keeping his premises clean and disinfected.

It was observed during the course of the epidemic that wind from the south and east, or that blowing from Baconsides to the more populous portions of the city, increased the violence of the disease and the rate of mortality, while when it came from the north and west there was a decided moderation in the severity of the symptoms.

Every shower of rain apparently aggravated disease. These showers were unaccompanied with thunder, of short duration, and the subsequent heat was intense. It having been stated by some physicians of local repute in the State that the disease which prevailed at Birmingham was not epidemic cholera, it is proper to state that the exhibition of the disease, both in its introduction, its mode of communicability, and in all its symptoms, closely and fully followed the history of cholera as it is laid down by authorities.

The active treatment of the premonitory diarrhoea was most successfully instituted, and the general expression of the profession of this city is that in not a single instance where this stage of the disease was treated, and where the patient followed fully the orders given, did the disease advance to its second stage; and so marked was this immunity that it is desired to add to the testimony on record, that by proper precautions, and the observance of hygienic laws, cholera attendants may enjoy the most perfect security from the disease.

The treatment adopted was the opium and mercurial. When the stomach seemed so inactive that nothing made any impression upon it, an emetic of mustard, salt, ginger, and pepper, suspended in hot water, in many cases produced a warm glow over the surface of the body in a few moments. For the relief of cramps which would not yield to ordinary remedies, a number of dry cups applied from the neck to the sacrum, over the spine, in every case in which they were used furnished the desired relief. The use of iced water ad libitum was found injurious; in many instances the unrestrained gratification of the thirst was followed by a fatal relapse. Ice and ice-water in small quantities and at short intervals was found most useful. Many of the cases were complicated with uraemia, and the majority of these died, although they were carefully treated. Diuretics produced no good results. No condition in life, sex, or age escaped. The sucking babe and those of extreme age suffered alike from its ravages.

Before closing this paper, justice demands that we should briefly allude to the heroic and self sacrificing conduct, during this epidemic, of that unfortunate class who are known as "women of the town." These poor creatures, though outcasts from society, anathematized by the church, despised by women and maltreated by men, when the pestilence swept over the city, came forth from their homes to nurse the sick and close the eyes of the dead. It was passing strange that they would receive no pay, expected no thanks; they only went where their presence was needed, and never remained longer than they could do good. While we abhor the degradation of these unfortunates, their magnanimous behavior during these fearful days has drawn forth our sympathy and gratitude.

In closing this brief record we desire to state that, in the experience of our observations, facts will not justify us in believing that any local conditions of the soil, or peculiarity of climate, or moisture of the atmosphere, or masses of decomposing debris, either animal or vegetable, can in or of themselves produce the specific poison of cholera, "but they are the hot-beds in and on which the cholera excretions having been placed, the poison is reproduced with fatal rapidity."

Birmingham, Ala., August, 1874.

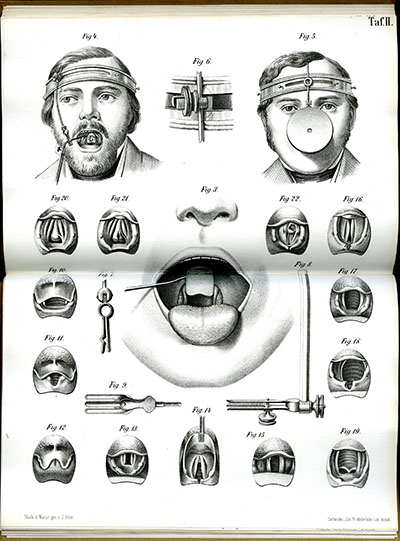

These illustrations of laryngoscopic instruments and views of the throat come from Die erste Ausrottung eines Polypen in der Kehlkopfshöhle (1862), by Victor von Bruns.On October 26, 2010, the Reynolds-Finley Historical Library received 125 rare and historical books related to the history of otolaryngology. The donation included important works by Casserio from 1601, Capivaccio from 1603, Aetius of Amida from 1549, and Conrad Schneider from 1664, as well as valuable works on the anatomy and diseases of the ear, nose and throat from the 18th and 19th centuries. This material, collected by Dr. Dennis G. Pappas, was formerly at the American Academy of Otolaryngology in Alexandria, Virginia, but has now come to Historical Collections at UAB for inclusion as a specially designated “Dennis G. Pappas Otolaryngology Collection” in the Reynolds-Finley Historical Library. This large acquisition of rare materials augmented books already donated by Dr. Pappas in this specialty, and he has continued to add to the collection since then.

These illustrations of laryngoscopic instruments and views of the throat come from Die erste Ausrottung eines Polypen in der Kehlkopfshöhle (1862), by Victor von Bruns.On October 26, 2010, the Reynolds-Finley Historical Library received 125 rare and historical books related to the history of otolaryngology. The donation included important works by Casserio from 1601, Capivaccio from 1603, Aetius of Amida from 1549, and Conrad Schneider from 1664, as well as valuable works on the anatomy and diseases of the ear, nose and throat from the 18th and 19th centuries. This material, collected by Dr. Dennis G. Pappas, was formerly at the American Academy of Otolaryngology in Alexandria, Virginia, but has now come to Historical Collections at UAB for inclusion as a specially designated “Dennis G. Pappas Otolaryngology Collection” in the Reynolds-Finley Historical Library. This large acquisition of rare materials augmented books already donated by Dr. Pappas in this specialty, and he has continued to add to the collection since then.

Click here to view Dr. Pappas's annotated bibliography of the collection. As the collection continues to grow, check back periodically to see if any new titles have been added. For additional information regarding the collection's holdings, search the UAB Libraries online catalog.

Also, on December 5, 2012, Dr. Pappas gave a Reynolds-Finley Historical Lecture, titled "The Turckish War of Laryngology: From the Dennis G. Pappas Collection," in which he provides historical background for many of the titles in the collection, as well as a discussion of the collecting process. Read the lecture transcript, or watch a video of the lecture below.

- Association of the Medical Officers of the Army and Navy of the Confederacy, Samuel Preston Moore Monument Committee. Surgeon General Samuel Preston Moore and the Officers of the Medical Departments of the Confederate States. Washington, D. C.: The Southern Cross, 1912.

- Atkinson, William B., ed. The Physicians and Surgeons of the United States. Philadelphia: Charles Robson, 1878.

- "Barton, Clara." Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary. 1971. Biography Reference Bank. Online. H. W. Wilson. Mervyn H. Sterne Library, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, 24 April 2007.

- "Barton, Clarissa Harlowe." American Reformers. 1985. Biography Reference Bank. Online. H. W. Wilson. Mervyn H. Sterne Library, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, 24 April 2007.

- "Barton, Clarissa Harlowe." Library of North American Biographies -- Volume 1 Activists. 1990. Biography Reference Bank. Online. H. W. Wilson. Mervyn H. Sterne Library, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, 24 April 2007.

- Blochman, Lawrence Goldtree. Doctor Squibb: The Life and Times of a Rugged Idealist. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1958.

- Chisolm, Julian John. Preface. A Manual of Military Surgery: For the Use of Surgeons in the Confederate Army. By Chisolm. Richmond, VA: West & Johnson, 1861. iii-v.

- "Cumming, Kate." Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary. 1971. Biography Reference Bank. Online. H. W. Wilson. Mervyn H. Sterne Library, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, 30 Oct. 2006.

- Dammann, G. E. Introduction. Medical Recollections of the Army of the Potomac. By Jonathan Letterman. Knoxville, Tenn.: Bohemian Brigade Publishers, 1994. i-iv

- Flannery, Michael A. Civil War Pharmacy: A History of Drugs, Drug Supply and Provision, and Therapeutics for the Union and Confederacy. New York: Pharmaceutical Products Press, 2004.

- Florey, Klaus, ed. The Collected Papers of Edward Robinson Squibb, M. D., 1819-1900, V. 1. Princeton, NJ: Squibb Corp., 1988.

- Freemon, Frank R. Microbes and Minie Balls: An Annotated Bibliography of Civil War Medicine. Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1993.

- Harwell, Richard. Introduction. The Journal of Kate Cumming: A Confederate Nurse, 1862-1865. By Kate Cumming. Ed. Richard Harwell. Savannah, Ga.: Beehive Press, 1975. vii-xviii.

- Heidler, David S., and Jeanne T. Heidler, eds. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2000.

- Holland, Mary A. Gardner, comp. Our Army Nurses: Interesting Sketches, Addresses, and Photographs of Nearly One Hundred of the Noble Women Who Served in Hospitals and on Battlefields During Our Civil War. Boston: B. Wilkins & Co., 1895.

- In Honor of Julian John Chisolm, M. D.: The Memoir Is Published upon the One Hundredth Anniversary of His Birth by Members of His Family and Former Associates. 1930.

- Kelly, Howard A., and Walter L. Burrage, Dictionary of American Medical Biography; Lives of Eminent Physicians of the United States and Canada, From the Earliest Times. New York & London: D. Appleton and Company, 1928.

- "Livermore, Mary Ashton Rice." American Reformers. 1985. Biography Reference Bank. Online. H. W. Wilson. Mervyn H. Sterne Library, The University of Alabama at Birmingham. 31 Oct. 2006.

- Norman, Jeremy M., ed. Morton's Medical Bibliography: An Annotated Check-List of Texts Illustrating the History of Medicine (Garrison and Morton). 5th Ed. Andershot, Hants, England: Scolar Press, 1991.

- Phalen, James Matthew, comp. "Chiefs of the Medical Department, United States Army, 1775-1940: Biographical Sketches." Army Medical Bulletin. 52 (1940): 42-46.

- Rutkow, Ira M. Introduction. A Manual of Military Surgery: Prepared for the Use of the Confederate States Army. By Samuel Preston Moore. San Francisco: Norman Pub., 1989. v-x.

- Rutkow, Ira M. Introduction. Resources of the Southern Fields and Forests, Medical, Economical, and Agricultural. By Francis Peyre Porcher. San Francisco: Norman Pub., 1991. v-ix.

- Rutkow, Ira M. Introduction. A Treatise on Hygiene: With Special Reference to the Military Service. By William Alexander Hamilton. San Francisco: Norman Pub., 1991. viii-ix.

- Smith, George Winston. Medicines for the Union Army: the United States Army Laboratories During the Civil War. New York: Haworth Press, 2001.

An ephemeris of materia medica, pharmacy, therapeutics and collateral information. Brooklyn: Charles F. Squibb, 1883-1906. Vols. 1 & 2.

Edward Robinson Squibb received his medical degree in 1845, and served as a naval surgeon from 1847-1857, where he was eventually became assistant director of the U.S. Naval Laboratory in New York. While in the service, he was exposed to the negative effects that impure medicines and drugs of variable quality have on both patients and the efficiency of the medical department. As biographer Lawrence Blochman notes, “Uniformity and purity became a lifetime passion with Dr. Squibb, a crusade which was to embrace all pharmacy” (Blochman viii). In 1856, Squibb invented an ether still apparatus that allowed for the production of better quality ether of more consistent strength and purity. His new process for distilling ether with live steam also made its use much safer, since an open flame was no longer needed to process the highly volatile chemical (Blochman vii-viii). The effectiveness of anesthesia was greatly improved by Squibb’s device. This was very fortunate to have by the war’s beginning.

Edward Robinson Squibb received his medical degree in 1845, and served as a naval surgeon from 1847-1857, where he was eventually became assistant director of the U.S. Naval Laboratory in New York. While in the service, he was exposed to the negative effects that impure medicines and drugs of variable quality have on both patients and the efficiency of the medical department. As biographer Lawrence Blochman notes, “Uniformity and purity became a lifetime passion with Dr. Squibb, a crusade which was to embrace all pharmacy” (Blochman viii). In 1856, Squibb invented an ether still apparatus that allowed for the production of better quality ether of more consistent strength and purity. His new process for distilling ether with live steam also made its use much safer, since an open flame was no longer needed to process the highly volatile chemical (Blochman vii-viii). The effectiveness of anesthesia was greatly improved by Squibb’s device. This was very fortunate to have by the war’s beginning.

Squibb left the navy in 1857 and set up a private pharmaceutical laboratory in Brooklyn, New York. Though he had already completed his military service before Civil War, Squibb did play an important part of the war effort by supplying pure, quality ether, chloroform and a variety of other medicines to the U.S. Army. He was also responsible for designing a new kind of light-weight pannier box (or medicine chest) which was used to distribute medicines to doctors working in the field (Smith 13-14). Essential to the establishment of Squibb’s lab as one of the primary army pharmaceutical suppliers was his good working relationship with military medical leaders. Chief purveyor for the U.S. Army, Richard S. Satterlee (1789-1880), impressed with the quality and skill of Squibb’s work, was responsible for many of the orders and contracts Squibb received from the army. After the war’s start, Satterlee requested that Squibb expand his laboratory to fill more of the army needs. Adequately convinced that the war would not be over in just a few months like many thought, Squibb re-located to a newly constructed two-story facility, and from there he supplied about one-twelfth of the army medical stores (Flannery 106). However, the army continued to need more and more supplies, and it was not long before government laboratories were set up to fill in the gaps of private industry. Now Squibb and other pharmaceutical manufacturers had competition to face. But in the end, government labs only supplemented private suppliers instead of destroying them as some feared (Flannery 114). In fact, the Civil War helped Squibb start what became a very successful pharmaceutical company, the Squibb Corporation, which is still thriving today. Also during the war, Squibb authored many articles in pharmacy journals, especially the American Journal of Pharmacy. The Reynolds-Finley Historical Library holds all war-year volumes of this publication.

After the Civil War, Squibb’s company emerged as a leader in the industry, a status it continued to hold after Squibb’s death in 1900. In addition to his highly-regarded business, Edward Squibb was also known for what Lawrence Blochman calls his “rugged idealism”. He was committed to pure, quality pharmaceutics manufactured and distributed to high professional and ethical standards. Never patenting his discoveries and inventions, Squibb held onto the notion that anyone who wished to use them to benefit mankind should have the ability. And he took up the cause of revising and completely revamping the United States Pharmacopoeia, a standard reference in the field. When the American Medical Association rejected his suggestion, Squibb founded a publication that could live up to his standards, An ephemeris of materia medica, pharmacy, therapeutics and collateral information. Although his two sons were named co-editors, most of the articles within this journal were written by Squibb himself. Distributed to professionals free of charge, this journal evaluated medicines, apparatuses and techniques, and was critical of greedy quacks (Florey xx; Blochman viii-ix). Issues were published every two months in order to keep professionals abreast of new developments throughout the year (Blochman 299). The Reynolds-Finley Historical Library holds the first two bound volumes of Squibb’s publication from 1882/1883 and 1884/1885.

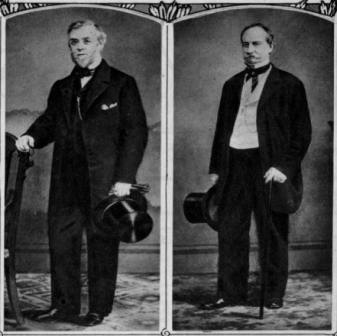

Image: Edward R. Squibb (pictured left) in 1864 alongside medical purveyor Richard S. Satterlee. Courtesy of the American Institute of the History of Pharmacy, Madison, Wisconsin.