Reynolds-Finley Section

Ackerknecht, Erwin H. A Short History of Medicine. Revised Edition. Baltimore & London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982.

Bookdealer notes, Reynolds-Finley Historical Library Vertical Files.

Clemens, Raymond & Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, 2007.

Nishimura, Margo McIlwain. Images in the Margins. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum; London: British Library, 2009.

Porter, Roy. The Cambridge Illustrated History of Medicine. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Sarton, George. Introduction to the History of Science, Volume II, From Rabbi Ben Ezra to Roger Bacon. Baltimore: Published for the Carnegie Institution of Washington by the Williams & Wilkins Company, 1931.

Walther, Ingo F. & Norbert Wolf. Codices Illustres: The World's Most Famous Illuminated Manuscripts, 400 to 1600. Koln; London; Los Angeles: Taschen, 2005.

Acknowledgement

The Reynolds-Finley Historical Library would like to thank volunteer, Maggie Gilchrist, a graduate of the UAB Department of English, for her assistance in scanning and photographing several of the manuscripts in this collection.

Materials

This illustration of three people seated at dinner comes from Arnold of Villanova's treatise on winemaking (Italy, 14th century), which is on vellum.As Raymond Clemens and Timothy Graham explain in their Introduction to Manuscript Studies, "Parchment is literally the substrate upon which virtually all knowledge of the Middle Ages has been transmitted to us" (p. 9). Parchment, or stretched animal skin, was used more frequently than paper in manuscript production until the fifteenth century. Though parchment can be made from a variety of animal skins, calfskin, also known as vellum, provided the best quality medium for medieval manuscripts and was still preferred by many for high end early printed books during the Renaissance. All three of the fourteenth-century manuscripts in the Reynolds-Finley Library are on vellum. The Rhazes manuscript, copied in the early 1400s from a 1388 translation, is composed of both paper and parchment, an example of the transition period between the two mediums. Finally, the manuscripts in the collection from the later fifteenth and sixteenth centuries are on paper. New paper production methods created in Italy in the late fourteenth century dropped the price of paper, setting the conditions for its preference at the arrival of printing in 1450.

This illustration of three people seated at dinner comes from Arnold of Villanova's treatise on winemaking (Italy, 14th century), which is on vellum.As Raymond Clemens and Timothy Graham explain in their Introduction to Manuscript Studies, "Parchment is literally the substrate upon which virtually all knowledge of the Middle Ages has been transmitted to us" (p. 9). Parchment, or stretched animal skin, was used more frequently than paper in manuscript production until the fifteenth century. Though parchment can be made from a variety of animal skins, calfskin, also known as vellum, provided the best quality medium for medieval manuscripts and was still preferred by many for high end early printed books during the Renaissance. All three of the fourteenth-century manuscripts in the Reynolds-Finley Library are on vellum. The Rhazes manuscript, copied in the early 1400s from a 1388 translation, is composed of both paper and parchment, an example of the transition period between the two mediums. Finally, the manuscripts in the collection from the later fifteenth and sixteenth centuries are on paper. New paper production methods created in Italy in the late fourteenth century dropped the price of paper, setting the conditions for its preference at the arrival of printing in 1450.

Illuminations

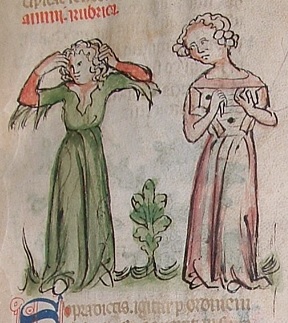

Illustration of two women from the Arnold of Villanova manuscriptThe term illumination originally referred to medieval book illustrations using gold and silver, which would illuminate the often religious subjects of the paintings. However, the term has come to refer to any illustrated work of the period. By the late Middle Ages, illuminations were no longer created by the scribe as seen in earlier medieval works, but instead, specially trained artists known as illuminators or miniaturists. It is interesting that extant receipts from book production indicate they were paid considerably less than scribes (Walther & Wolf, p. 21), despite the beauty and intricacy of their art and the value it added to a manuscript. Nevertheless, in the pre-printing age, the knowledge conveyed through the scribe's text was the essential part of the book. Whereas the names of scribes were often recorded, the illuminators' almost never were.

Illustration of two women from the Arnold of Villanova manuscriptThe term illumination originally referred to medieval book illustrations using gold and silver, which would illuminate the often religious subjects of the paintings. However, the term has come to refer to any illustrated work of the period. By the late Middle Ages, illuminations were no longer created by the scribe as seen in earlier medieval works, but instead, specially trained artists known as illuminators or miniaturists. It is interesting that extant receipts from book production indicate they were paid considerably less than scribes (Walther & Wolf, p. 21), despite the beauty and intricacy of their art and the value it added to a manuscript. Nevertheless, in the pre-printing age, the knowledge conveyed through the scribe's text was the essential part of the book. Whereas the names of scribes were often recorded, the illuminators' almost never were.

A plate, a wine-glass, and a fish on a dish, upon a table laid with a cloth, from Arnold of Villanova's manuscriptIlluminators were skilled artists, but the process was very technical as well. They usually created preliminary artistic designs that were recreated on the text using reproduction methods such as an early form of tracing paper. But some were copied from pattern books or the work of respected illustrators. These illustrators were also trained in the preparation of gold leaf and the concoction of paint from minerals, plants, animals and binding mediums (Walther & Wolf, p. 22). See the 26 miniature illustrations from Arnold of Villanova's Regimen Sanitatis ad Regem Aragonum in the Reynolds-Finley Library for examples of the art of illumination.

A plate, a wine-glass, and a fish on a dish, upon a table laid with a cloth, from Arnold of Villanova's manuscriptIlluminators were skilled artists, but the process was very technical as well. They usually created preliminary artistic designs that were recreated on the text using reproduction methods such as an early form of tracing paper. But some were copied from pattern books or the work of respected illustrators. These illustrators were also trained in the preparation of gold leaf and the concoction of paint from minerals, plants, animals and binding mediums (Walther & Wolf, p. 22). See the 26 miniature illustrations from Arnold of Villanova's Regimen Sanitatis ad Regem Aragonum in the Reynolds-Finley Library for examples of the art of illumination.

Marginalia

Illustration in the margin of Petrus Peregrinus' Tractatus de Magnete (England, 14th century)"Unpredictable, topical, and often irreverent, like the New Yorker cartoons of today, marginalia must have been a source of great delight for medieval readers," says Margot McIlwain Nishimura in her book Images in the Margins. Sometimes relevant to the content, marginalia are just as often playful and whimsical manifestations of imagination with no connection to the subject matter of the serious works they accompany. Created using the same materials and techniques as other illuminations, they were clearly original to the manuscripts but themed less similar to the particular works they inhabit than to marginalia themes found throughout manuscripts, primarily those of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

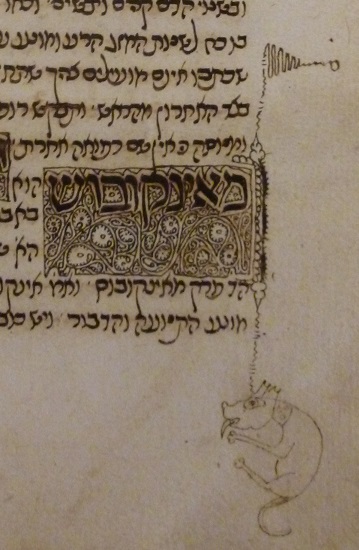

Marginalia from Rhazes' Al' Mansuri (Portugal, 1388)Animals and humans falling off the page and strange hybrid creatures are common. The Rhazes manuscript at the Reynolds-Finley Library is decorated with a number of interesting marginalia, such as hybrid figures and a dog suspended from rubricated letters.

Marginalia from Rhazes' Al' Mansuri (Portugal, 1388)Animals and humans falling off the page and strange hybrid creatures are common. The Rhazes manuscript at the Reynolds-Finley Library is decorated with a number of interesting marginalia, such as hybrid figures and a dog suspended from rubricated letters.

Clear markings of page layout, from Medical MiscellanyWhereas monks produced manuscripts almost exclusively for most of the medieval period, beginning in the thirteenth century, the process became more secularized.

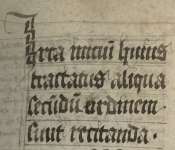

Clear markings of page layout, from Medical MiscellanyWhereas monks produced manuscripts almost exclusively for most of the medieval period, beginning in the thirteenth century, the process became more secularized. Anglicana bookhand, Petrus Peregrinus manuscriptThe growing industry of book production now split the work between several types of specially trained craftsmen: scribes, rubricators, and illuminators. Scribes were responsible for ruling the parchment or paper, page layout, and copying the text. Trained in the handwriting styles of the day, their scripts are helpful in determining the date and location of book production. For example, Petrus Peregrinus' Tractatus de Magnete was written in an Anglicana bookhand, which was common in England in the thirteenth through fifteenth centuries.

Anglicana bookhand, Petrus Peregrinus manuscriptThe growing industry of book production now split the work between several types of specially trained craftsmen: scribes, rubricators, and illuminators. Scribes were responsible for ruling the parchment or paper, page layout, and copying the text. Trained in the handwriting styles of the day, their scripts are helpful in determining the date and location of book production. For example, Petrus Peregrinus' Tractatus de Magnete was written in an Anglicana bookhand, which was common in England in the thirteenth through fifteenth centuries.

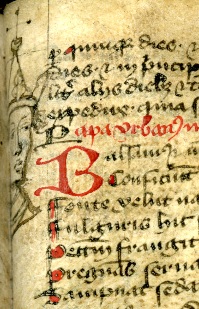

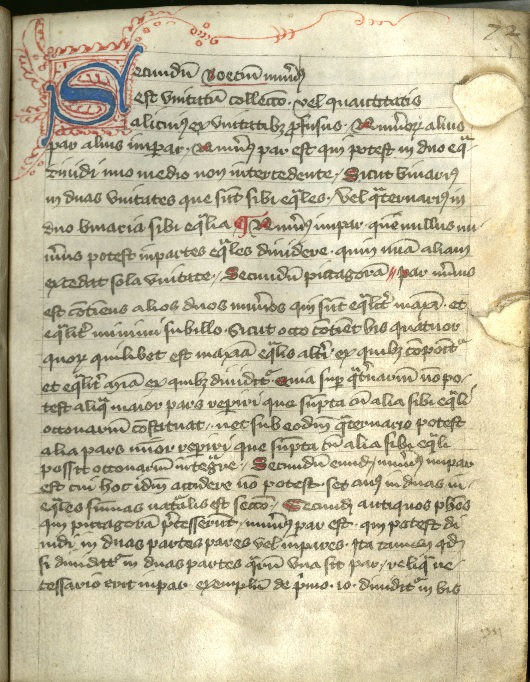

Pen-flourished initial from the Bernard of Gordon manuscriptIn laying out their manuscripts, scribes left empty spaces for rubricators and illuminators to fill in with decoration. Rubricators were responsible for the colored initials and titles that initiate separate tracts or chapters. Usually done in red (but also seen in blue or green), the word rubrication comes from the Latin word for red, rubrico. Styles of rubrication also help date texts. For example, the red and blue pen-flourished initials extending down the margins, as seen in the manuscript of Bernard of Gordon, were typical of Gothic manuscripts of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries (Clemens and Graham, pp. 26-27).

Pen-flourished initial from the Bernard of Gordon manuscriptIn laying out their manuscripts, scribes left empty spaces for rubricators and illuminators to fill in with decoration. Rubricators were responsible for the colored initials and titles that initiate separate tracts or chapters. Usually done in red (but also seen in blue or green), the word rubrication comes from the Latin word for red, rubrico. Styles of rubrication also help date texts. For example, the red and blue pen-flourished initials extending down the margins, as seen in the manuscript of Bernard of Gordon, were typical of Gothic manuscripts of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries (Clemens and Graham, pp. 26-27).

Space for illustrations in the Arnold of Villanova manuscriptLarger spaces within the text were left for illustrations to be done by an illuminator or miniaturist. Proof that manuscripts were produced this way is seen in examples such as the Reynolds-Finley Library's manuscript of Arnold of Villanova where empty spaces still remain after pages of frequent illumination.

Space for illustrations in the Arnold of Villanova manuscriptLarger spaces within the text were left for illustrations to be done by an illuminator or miniaturist. Proof that manuscripts were produced this way is seen in examples such as the Reynolds-Finley Library's manuscript of Arnold of Villanova where empty spaces still remain after pages of frequent illumination.

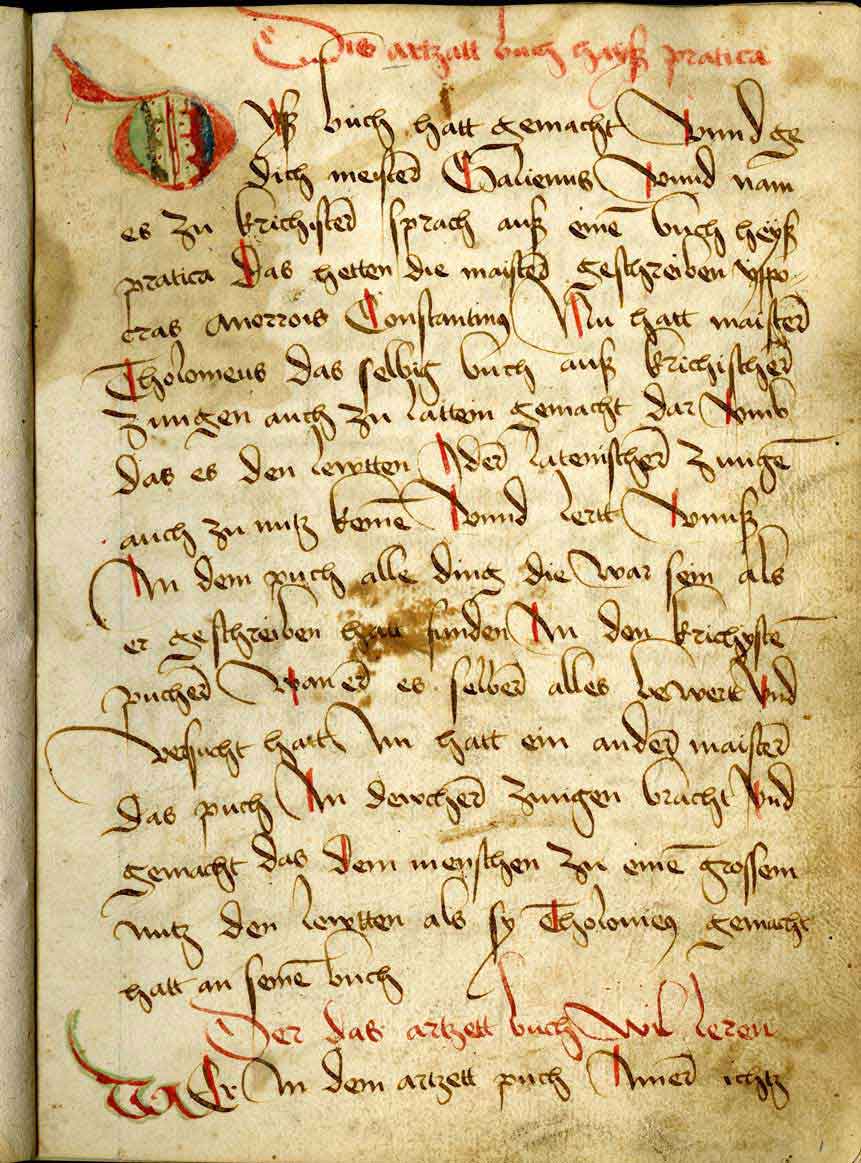

Leaf 1 recto, from Dis Artzatt Buch Gross Pratica (1489)During the Early Middle Ages, also known as the "Dark Ages" (from the fall of the Roman Empire to about 1000 A.D.), when ancient Greco-Roman knowledge and culture was neglected and nearly forgotten in Europe, the Arabs preserved and built upon the scholarship of the great medical writers of the classical world, such as Galen (129-199 AD) and Hippocrates (c. 460-370 BC). Greek culture still flourished in the Near East when the Arabs migrated to the area from Syria in the 7th century. Later they took Greek medical texts into Persia and other parts of the Middle East, translating them first into Syriac, and then into Arabic.

Leaf 1 recto, from Dis Artzatt Buch Gross Pratica (1489)During the Early Middle Ages, also known as the "Dark Ages" (from the fall of the Roman Empire to about 1000 A.D.), when ancient Greco-Roman knowledge and culture was neglected and nearly forgotten in Europe, the Arabs preserved and built upon the scholarship of the great medical writers of the classical world, such as Galen (129-199 AD) and Hippocrates (c. 460-370 BC). Greek culture still flourished in the Near East when the Arabs migrated to the area from Syria in the 7th century. Later they took Greek medical texts into Persia and other parts of the Middle East, translating them first into Syriac, and then into Arabic.  Beginning of the fourth treatise within Medical MiscellanySoon the Arabs were building on this classical tradition, producing important original contributions to medical advancement by figures such as al-Razi (ca. 860-ca. 930 AD) and Ibn Sina (980-1037 AD), known in the West as Rhazes and Avicenna respectively. During the reawakening of Europe in the Late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, ancient classical and medieval Arabic medicine was brought to Europe and translated into Latin. The writings of Galen, Hippocrates, Rhazes, Avicenna and other greats from these traditions remained authoritative in medicine well into the Early Modern period.

Beginning of the fourth treatise within Medical MiscellanySoon the Arabs were building on this classical tradition, producing important original contributions to medical advancement by figures such as al-Razi (ca. 860-ca. 930 AD) and Ibn Sina (980-1037 AD), known in the West as Rhazes and Avicenna respectively. During the reawakening of Europe in the Late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, ancient classical and medieval Arabic medicine was brought to Europe and translated into Latin. The writings of Galen, Hippocrates, Rhazes, Avicenna and other greats from these traditions remained authoritative in medicine well into the Early Modern period.

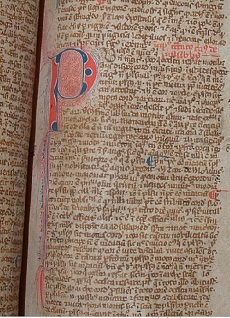

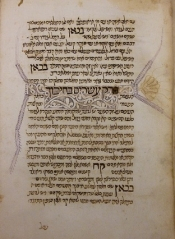

Illuminated page from the Ninth Book of the Al-MansuriSeveral of the manuscripts in the Reynolds-Finley collection are translations of these writers’ works. For example, the German manuscript, Dis Artzatt Buch Gross Pratica (1489), though written down by Bernhardus Dieterich, is ascribed to Galen in the opening paragraph, and Bernhardus also names both the Arabic and Latin translators. The medical treatises that comprise Medical Miscellany include selections by Galen, Hippocrates, Avicenna and Mesue (Ibn Masawaih). The presence of both classical and Arab authors in this volume reflects the transfer of these traditions together into Europe. Also included in the collection is a Portuguese Hebrew manuscript of Rhazes, Ninth Book of the Al-Mansuri, translated into Hebrew from Latin by Jewish physician Tobiel ben Samuel de Leiria in 1388, illustrating the role of Jewish scholarship in the transfer of Arabic medicine.

Illuminated page from the Ninth Book of the Al-MansuriSeveral of the manuscripts in the Reynolds-Finley collection are translations of these writers’ works. For example, the German manuscript, Dis Artzatt Buch Gross Pratica (1489), though written down by Bernhardus Dieterich, is ascribed to Galen in the opening paragraph, and Bernhardus also names both the Arabic and Latin translators. The medical treatises that comprise Medical Miscellany include selections by Galen, Hippocrates, Avicenna and Mesue (Ibn Masawaih). The presence of both classical and Arab authors in this volume reflects the transfer of these traditions together into Europe. Also included in the collection is a Portuguese Hebrew manuscript of Rhazes, Ninth Book of the Al-Mansuri, translated into Hebrew from Latin by Jewish physician Tobiel ben Samuel de Leiria in 1388, illustrating the role of Jewish scholarship in the transfer of Arabic medicine.